COMPLETELY

MISSING KUBRICK

The

flood of obituaries and "tributes" to Stanley Kubrick was strangely disrespectful

writes the director's longtime friend, while the reviews of Eyes Wide Shut

were even worse: cynical, condescending, and stunningly wrongheaded. Here's

what the critics just didn't get

BY

MICHAEL HERR

A couple of days after

Stanley Kubrick's funeral, the London Times ran a story about a 67-year-old

former housekeeper for the Kubrick family named Betty Compton, who was planning

a memoir. "He was eccentric and paranoid," she said, "but he was not a lunatic."

She added, "If you didn't patronize him, he was great to work with."

I found this to be true.

The following week, Frederic

Raphael, Stanley's palpably unhappy collaborator on the screenplay for Eyes

Wide Shut, had the proposal for his memoir on publishers' desks. The book

that swiftly followed made a display that was hard for some people to take.

It wasn't just that it was so antagonistic to Stanley, or even that it was

so bitter and self-humiliating, but that it was so unfailingly patronizing.

Stanley, we gather, hadn't been sufficiently deferential to Raphael's credentials,

to his academic attainments and his immense store of knowledge, his often

unfortunate command of foreign words and phrases and the insolent presumption

of superiority that came along with it all, however unentitled. We read of

Stanley the tyrant, Stanley the obsessive perfectionist, cold Stanley, secretive

Stanley, unhelpful Stanley, and a new one particularly distasteful because

it was so gratuitously trumped up as to look like mere projection -Stanley

the self-hating Jew.

"They're either at your

throat or they're at your feet," Stanley said, recalling a catchphrase that

was current in European diplomatic circles after the Second World War. Then

it referred to the Germans; now he was talking about critics and commentators

on the culture in general, entertainment journalists: high-, low-, but mostly

middlebrow, generally contentious and misinformed, sometimes flagrantly intellectual

media mavens. Whenever he possibly could he'd try to put one of them in his

pocket, so to speak (there are no ex-chess masters), but the deformed perception

of him among so many of them, and the fixated way that it operated, was at

best uncomfortable for him, even though he was aware that by being the way

he was, he was only nourishing it. He understood both the principle of complete

cover and the cost of it. Nevertheless, he was a sensitive guy (I can hardly

believe that I feel the need to say this, and so explicitly), and his feelings

could be hurt. He wasn't especially touchy; it's hard to imagine him sulking,

or brooding about anything other than work. He wasn’t as fragile as glass,

and the change of seasons didn't make him weep, but stupidity and injustice

hurt his feelings, and it wasn't even as personal as you might think.

When I first knew Stanley,

I told him that when I had come to New York in the early 60s I worked briefly

as the film critic (unpaid) of a magazine called The New Leader ("You

mean they didn't pay you anything?" "They paid for the movie tickets." "Gee,

Michael ... Did you at least have a percentage of the profits? An expense

account? Luncheon vouchers?") I told him that one of the movies I'd reviewed

was Lolita, so naturally he had someone in New York go down into the

catacombs beneath the Public Library to find the review and send it to him.

He liked it. I'd given it a rave. I gave it a much better review than Stanley

himself did.

|

INSTANT

REPLAY

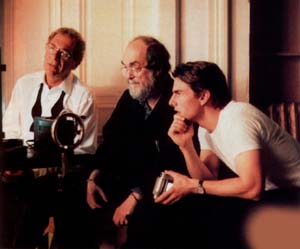

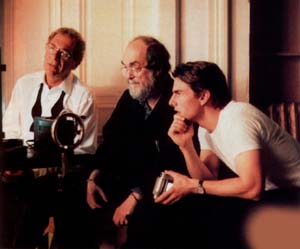

Sydney

Pollack and Tom Cruise watch the rushes of one of their scenes together

with the director.

|

We read

of Stanley the tyrant,

Stanley the obsessive perfectionist, cold Stanley, secretive Stanley,

unhelpful Stanley.

|

I was useless as a critic.

I had followed Manny Farber at the magazine, one of the best of all writers

on movies, as I was reminded when a collection of his criticism called Negative

Space was reissued two years ago. I was out of my element, and out of

my depth. My reviews weren't very good to begin with-I seem to remember claiming

that a Japanese movie called The Island was such a moving experience

that I didn't realize until it was over that there hadn't been a word of spoken

dialogue-and I made matters worse by disliking a series of fashionable (for

five minutes) European films, and then by falling for a bunch of Hollywood

movies that were nothing more than studio product that looked good, or were

true-to the code genre pictures, or that otherwise amused me. (Most of the

films from all these categories, foreign and domestic, have vanished, gone

as if they'd never been made.) I didn't last very long, less than a year,

but in that short time I came to hate going to the movies, an incredible thing

for someone who before then had never seen a movie that he didn't like.

I remember this whenever

I think about the lives that critics must lead, particularly movie critics,

and even more particularly the old-school cineasts, the back-of-the-book veterans

who still write film criticism after 40 years and more, yet without having

developed light and playful minds; telling other people where they went wrong,

living under the day-to-day strain of having to come up with another superlative,

one more pejorative, while still maintaining their credibility. And I know,

because I've been there, that there is a hellworld where you're always expected

to have an opinion about everything all the time: a judgment, a take - a "view,"

in the most ordinary sense of the word. "I've been reading some of these reviews,"

Stanley said, "and boy, Michael ... remember that old radio program It

Pays to Be Ignorant?" This was after Full Metal Jacket opened,

and he was warming to a few remarks about specific critics. "Oh well anyway,

at least they try and spell my name right," he said.

As a friend of his, I

never used to care that much when I'd read some of the crap they wrote about

him, but now that he's dead, I have to say, it upsets me. Of course, it's

always painful to see a great artist belittled by fools, simply because of

their mean, confused, negative conjectures, misconception layered upon misconception,

awesomely committed to misconception. It can never turn out well when a square

takes a hipster for his subject. Essentially incapable of regarding him as

anything other than the weird phobic controlling maniac of fable more than

legend, they hold stubbornly, I would even say stupidly, to their assumptions,

often objecting to him personally, to his secrecy and his silence and even

his wealth. (There was even some suspicion about his "mysterious" death, as

though the great elusive could never have been overtaken by anything as prosaic

as a heart attack.) Accepting and circulating the presumptions about Stanley's

pathology, they have themselves acquired a pathological dislike of him and

his work. Never mind for the moment that many of them are actually good critics,

people I've read for years and continue to read. They get that Stanley bit

between their teeth, and they're off like a bugaboo strapped to a hobbyhorse.

The strangely contentious

and extremely disrespectful tone that lurked inside so many of the obituaries

and tributes was unpleasant to the people who loved Stanley, but not surprising.

Then Eyes Wide Shut came out, and then the reviews, and the inescapable

flood of what used to be called "think pieces": The New Yorker, The New

York Times (with the notable exception of Janet Maslin, whose passionate

appreciation of the film was even rumored to have been a catalyst for her

resignation from that paper), The New York Review of Books, The

New Republic, same old same old, Ill Seen Ill Said. There aren't

many spectacles more dispiriting than this one, the culture-critical smart

set, united in aversion, dreadfully putting on their thinking caps.

As a not-so-pure product

of the 60s, I've often wondered whether over the long run the sexual freedom

of those years didn't numb more genitals than it inflamed, more than all the

prohibitions of all the decades that went before. The actual realization,

after so much collective longing, of a genuine liberation of erotic impulse

and expression pumped a marvelous vitality into the culture; many modes and

views that were (allegedly) undreamed of a generation before, or even a year

before, were out there frolicking in the open air, swimming naked in the mainstream,

visible, televised, explicit, rampant. But what if freedom isn't just another

word for nothing left to lose, but something that's lost whenever you mistake

a carnal matter for a spiritual matter? If there was a liberation 30 years

ago, why now all this confusion, rancor, pornography?

|

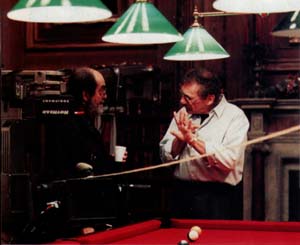

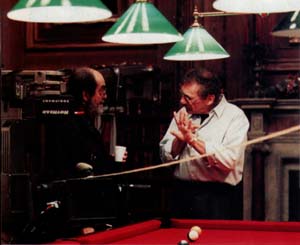

BRAINSTORMING

Kubrick and the director Sydney Pollack, who acts in this film, hammer

out the long, much-discussed pool-table scene.

|

I don't

even know what the scene's supposed to be about, unless, as I suspect,

it's really just about the red pool table.

|

The misbegotten and briefly

famous media campaign for Eyes Wide Shut is already forgotten, except

by entertainment-marketing professionals, and then only for the devastation

of its backfire. There were no fast-food tie-ins, but no movie can open any

longer without an appeal to whatever is less than wholesome in us. This one

opened behind sex and supercelebrity, although not even Tom Cruise could save

it as product, and sex was its downfall. It was a bad idea in this salacious

climate to toy with people's expectations by suggesting that Eyes Wide

Shut was going to be the sexiest movie ever made, a Last Tango in Paris

for our sex-drunk times, instead of telling the extremely risky truth

and saying that it was merely one of the most beautiful.

"Art-phobia is now the

dominant sensibility of the official culture, and art-phobia annihilated Stanley

Kubrick's autumnal work," Lee Siegel wrote in Harper's Magazine a couple

of months after the debacle, eloquently taking the words right out of my mouth,

and speaking for what he believes to be a great film. Bravely, he continues,

"Genuine art makes you stake your credulity on the patently counterfeit,"

a gambit he claims the critics didn't even consider, let alone dare. (Film

critics insensible to mise en scéne are not a recent phenomenon; no

one who remembers Bosley Crowther, film critic for The New York Times

from the 40s through the 60s, can think that artphobia in "high places" is

new.) "For they fear that if they surrender themselves to the work's strangeness,

they will seem vulnerable and naive and intellectually unreliable." Instead

of responding to the work, they responded to the hype, trashing the movie

both as a commodity and as an entertainment. Siegel goes on in understandable

indignation to explain how a film so ravishing and benign and certainly strange

could have fallen through so many cracks in the culture.

Stanley was hardly blameless

in this, and I suppose it's possible that if he thought he could get away

with it, at this time and in this country, then maybe he was out of it. We

can take it as a given that he controlled the publicity and marketing strategies

until the hour he died. I don’t know who became the commander afterward,

or whether it was a shared command, but there was an excessive use of firepower,

and many missed targets, and the collateral damage was all to the movie. Some

critics loved it, but most, often speaking for the public, wrote so scornfully

that it was difficult to keep from forming a snotty attitude myself, one that

said that people who love movies love Stanley's movies, and those who don't,

don’t.

After busting him all

these years for his nihilism, they busted him now for his belief, often with

a blend of stridency, cynicism, and po-faced hypocrisy: "Kubrick: A Sadness"

(boo hoo) from The New Republic and "A stiff, alas" (oh boy oh boy)

from The New Yorker. The tears were positively crocodilian, and more

than one commentator, looking back a few months later on many of those first

reviews, remarked on the disagreeable quality of self-congratulation that

played so solemnly through them. (One critic spoke of Stanley's "brutal voyeurism,"

but it was only voyeurism, and could he direct me to a director who isn't

a voyeur?) They wrote as if they'd been cheated; and they wrote facetiously,

condescendingly, insultingly. But you can't cheat an honest man, and I'm fairly

certain that you can't insult a work of art. All you can do is damage its

reputation at a decisive moment, and seriously hurt its box office.

Expecting sex, promised

sex in writing, critics and commentators and audiences wanted sex. They were

outraged that the orgy didn't turn out to be the Fuckorama of their not unreasonable

expectations, that the stars didn't get all the way down so we could watch.

What they got instead was an eroticism so deeply embedded in memory and imagination

that the more physical it becomes, the less erotic it is. They got the sex

that's indivisible from death, and an orgy that was certainly fleshly enough,

yet anaphrodisiac, liturgical. Tom Cruise wanders the streets of New York

(static and underpopulated streets, according to the critical consensus) for

the better part of two days and nights, and except for one time, with his

wife and offscreen, can't manage to get laid; not with the squirming sirens

that he meets at a party (the stimulating Gayle and the lovely Nuala, who

spells her name out for him and makes it sound like a new word for pleasure),

not with a beautiful, kindhearted hooker (he pays her anyway) or a sweet and

possibly simpleminded nymphet paradigm of natural sex, not even at an orgy,

even though everywhere he goes, everything that moves comes on to him - man,

woman, and child.

Neither, in spite of a

few dark shadows and some spooky music, did they get the advertised thriller.

Instead, they got mystery, much more problematic, a film of curious incident

and haunting color, of city streets at night that look like they've had a

spell put on them, of masks and Christmas trees, of ringing telephones and

flunkies approaching with requests from their masters, apparent interruptions

that are really cues for the next passage to begin. The subject isn't sex

and thrills but marriage and fidelity; Fidelio is the password and the presiding

spirit of the piece.

In the Mozart comedies

(so called), the frantic and unfunny farce on the stage tells one story while

the music tells the real one. It's the same in each of them, those incomparable

poems of fidelity and honor struggling for parity in a fickle, whorish world;

chastity besieged and betrayed, a lover's faith tossed on the table like stakes

in a careless wager, Cosi Fan Tutte; very amusing, for sadists and

cynics at any rate, and irresistible to artists. Arthur Schnitzler caught

the mordant gist of it in Traumnovelle,

the book on which the movie was based, and Stanley transposed it to a far

warmer key, changing its meanings. It's not like Don Giovanni at all, although

there's an homage to the don in the character of Sandor Szavost (Stanley's

little Hungarian joke, played with cheesy charm by Sky Dumont). Eyes Wide

Shut is much more like The Magic Flute, a fairy tale, with a dangerous,

possibly ethereal quest successfully accomplished, a curse lifted, and the

semblance of a happy ending. And like the best fairy tales, enchantment provides

the propulsion, and death is the ballast. The only Mozart actually on the

soundtrack is from the Requiem.

In place of the fastidious

and unsettling creepiness of Traumnovelle

(which isn't the sexiest novella ever written, just one of the most disturbing),

Stanley created a deep charm which hardly exists in the text but which can

be found in the films of Ernst Lubitsch, Max Ophüls, and Josef von Sternberg,

a couple of dreamy Europeans and an inspired pretender. This alone was enough

to set the New York quadrant smirking. Complaining, in so many words, that

like all of his movies, Eyes Wide Shut didn't keep telling them what

they were supposed to be feeling, they said that it was without feeling. Because

it was in a style they hadn't seen before, they said that it had no style.

(Or in one instance, objected that it was "stylized," as though stylization

had suddenly become unacceptable in film.) They even said that it didn't have

a story, but it did, and a good one, the one about the man who loved his wife.

Two camps have always

formed around each of Stanley's movies, and no one in either camp could ever

imagine what the other camp thought it was seeing. A lot of people were (and

remain) indignant over 2001 and what they considered its hippy-dippy

obfuscations. Barry Lyndon was written off as nothing more than a coffee-table

movie, a day at the Prado without lunch. A Clockwork Orange was a moral

abomination altogether, while less than 10 years before, Dr. Strangelove

was felt to be an unspeakable breach of etiquette. In the case of Eyes

Wide Shut, the camps were made up of those people who knew within minutes

that they were watching a dream film and those who didn't. Grudgingly conceding

that Stanley possessed great imagination, they could never see how fanciful

that imagination always was.

I have no idea how much

of Eyes Wide Shut is meant to be taken literally as a dream, or a string

of occurrences on the road running in and out of a dream, or a story with

no logic but dream logic. Stanley always spoke of movies as dreams, dreams

about dreams, including daydreams and nightmares (although I don't think he

ever spoke of them as only dreams), and never made any distinction-this is

the kind of materialist I think he really was-between a dream and a vision.

But the very word "dream" and the activity it represents have become gruesomely

devalued by television, where when they speak of dreams they mostly mean some

forlorn wish they want fulfilled, feel entitled to have fulfilled, something

grossly material and equally impossible, nothing like a dream at all.

One critic called

Eyes Wide Shut a series of erotic misadventures," completely missing the point.

In Eyes Wide Shut,

the Shostakovich waltz begins, a melancholy pastiche of a waltz, like a rose

with a canker in it, as Alice steps between two pillars and lets her dress

fall to the floor, in an apartment that was considered by some to be much

too opulent, unimaginably opulent, for a New York doctor and his wife to be

able to afford. Nevertheless, they move around it as if they owned the place,

joined in something that would immediately be identified as domestic intimacy

if this weren't a Stanley Kubrick film. Not concerned with blood and iron

this time, or conflict on an international or cosmic scale, Stanley was in

the mood for love, he made a movie that was all for love, a high comedy about

a couple crossing that sector of the connubial minefield where the devices

are especially well buried. It's the situation that got him when he first

read Traumnovelle, and it was cooking up in his head for more than

30 years. He turned his gaze upon a conjugal arrangement composed of trust

and complacency in equal measure, which is about to be tested in the fire.

Dr. Bill Harford can tell

his wife that she looks perfect without even looking at her because he loves

her and he knows that she's perfect; it's one of the things about her that

he takes for granted. He asks her if she's seen his wallet (the magic wallet

that will produce thousands of dollars over the nod three nights and that

contains his amulet, the New York State Medical Board card which will open

many doors and relax many suspicions-it's O.K., he's a doctor). She tells

him that the wallet is on the bedside table. She removes her glasses, he turns

off the waltz, and they step out into the highly eroticized, boundlessly suggestive

New York Yuletide night.

According to the legend,

there was a fir tree in Eden that died when Eve ate the apple, and flowered

again at the Nativity. And Stanley, with his German family connections, European

sensibility, and wide voracious reading, must have come across the story of

Count Otto, called Stone Heart by his subjects because he never loved a woman,

until he met the supernaturally beautiful Queen of the Fairies. She became

his consort, and brought as her dowry a Christmas tree hung with gems and

golden daggers, and said that she would be his just as long as he never uttered

the word "death," which wasn't long.

There's a Christmas tree

in Bill and Alice's apartment, there's a Christmas tree in the room where

a presumably Jewish patient of Bill's has just died (and where the bereaved

daughter devours Bill with hungry kisses as she embraces him at the feet of

her father's corpse), and there's one in the apartment of the prostitute that

Bill encounters in his downtown wanderings. (The music in this scene is "I

Got It Bad and That Ain't Good." We find out later that she's H.I.V.-positive,

and that Bill missed a bullet by not fucking her. Good thing his cell phone

rang.) A tree stands in the foyer of Victor Ziegler's town house, which looks

like the manger where Mammon was born, and where a dream party is going on,

more of a midwinter Saturnalia than a Christmas party. There's a tree in almost

every room in the movie, except at the estate where the orgy is held, and

that's surrounded by pines. There's one in Bill's office and another in the

hospital where he goes to view the body of the mysterious woman who may have

given her life for his, or who may have just been a hooker with a drug problem,

"the one with the great tits who OD'd in my bathroom," as Victor so tenderly

says later, when the mask falls off and his monster leaves its box.

Watching Eyes Wide

Shut, I remembered the producer of some of the most successful action

movies of the 80s, who said that he didn't want any women in his pictures

unless they were either naked or dead. The few women who aren't already naked in

Eyes Wide Shut are ready to become naked with just a glance from Bill;

their clothing is just another illusion. And while there's only one dead woman

in the story, there are steaming succubi and hungry animae and women who seem

to look at Death as the guy they're really interested in-they're hot to go

and they want to take somebody with them.

"Don't you want to go

where the rainbow ends?," Gayle and Nuala ask Bill at the party. As far as

they're concerned, it ends in bed with them, but he is called away, "summoned."

(He doesn't find it later in Rainbow Fashions either, the comically sordid

and utterly magical costume shop where Mr. Milich, a relic of old Europe,

is doing his thing: "What on earth is going on here?" he bellows in mock outrage,

knowing exactly what is going on. When he uncovers the two fantastical Japanese

men dressed only in wigs and bikini briefs panting after his under-age daughter,

he cries, "Have you no sense of decency?" Then he sells her to them.)

|

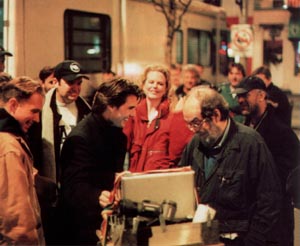

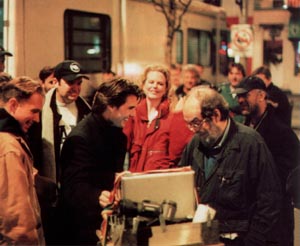

STREET

SCENE

The

director, the stars and the crew, at work on the set built for New York

street scenes.

|

I never

used to care that much when I'd read some of the crap they wrote about

him, but now that he's dead it upsets me.

|

What happens at the Christmas

party, and over the next couple of nights, is all in consequence of Bill's

leaving his wife for a minute to follow the elusive and somewhat devilish

Nick Nightingale (a great fairy-tale name), a med-school dropout and piano

player for all occasions. Then Nick's summoned away, vanishes, and as Bill

negotiates his perilous way between lascivious Gayle and tantalizing Nuala,

Alice waltzes with her eager Hungarian. As Bill looks with professional detachment

at the naked and comatose form of one of Victor's girlfriends ("Alice, I'm

a doctor," he reminds his wife later; she's hardly reassured), Sandor tries

to seduce Alice. And even though she breaks away from him to look for her

husband, as the orchestra plays "I Only Have Eyes for You," Sandor seems to

have impregnated her anyway. She leaves the party bearing an imp who will

be born the next night, when, stoned and provoked by Bill's presumptions about

her and women in general, and exhausted by what it is he thinks that women

really want, she makes her "confession": her story about the stranger, a naval

officer she saw only in passing the summer before, and how in a moment she

wanted him so completely that she would have been willing to leave her husband

and child forever to spend one night with him. And just like that, spontaneously,

she gives birth to unwanted, necessary Honesty and its very unpleasant twin,

Jealousy. The movie that running in Bill's head is the one that everybody

wanted to see in the first place.

Revenge fucking may not

be the sweetest sex, the most satisfying, but it's the most urgent. It's also

almost always a wretched futility, and it requires good character and better

luck to avoid it. Tied to a whipping post he didn't even know existed before,

Bill goes off on a two-day trajectory through the desire realms without ever

understanding what it is that he actually desires. He experiences plenty of

sexual abrasions he's gay-bashed, importuned, receives an unwanted confession

of love, and has his life threatened-but never sex. He keeps leaving the dugout

but he never steps up to the plate. (One critic called it "a series of erotic

misadventure completely missing the point, and another presumed to know what

"the audience" had learned about marriage and sex from the films of the past

century, particularly from Bergman, ignoring all that this same audience had

forgotten in the more than 25 years since the movies became Balkanized by

television.)

Without making ignorant

assumptions about the actual sex life of Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman (the

focus of so much speculation in the coverage and even the reviews of Eyes

Wide Shut), they certainly proved to my satisfaction that they knew how

to play a beautiful, happily married couple in love in a movie. No one could

have been surprised by Nicole Kidman's acting, but once the reviewers had

paid tribute to Tom Cruise's status as a major movie star, most went on to

dismiss his amazing performance. Like Ryan O'Neal, Jack Nicholson, and Matthew

Modine before him, Tom Cruise gave Stanley his money's worth. He created the

perfect vehicle to carry one of the film's most original and shocking themes.

In ways that Schnitzler never even thought about, Eyes Wide Shut challenges

the ancient and poisonous canard that the erect male member has no conscience.

Stanley Kubrick and rainbows,

Stanley Kubrick and party fights, Stanley Kubrick on behalf of love and marriage,

chastity, and the secrets of women-what on earth is going on here? For a movie

that offers glimpses of a lurid nighttime underworld, and that has a powerful

current of morbidity running through it, Eyes Wide Shut has a remarkably

sunny disposition. There's a sweetness to most of the people in the film,

and to most of the performances. (It was probably bad for Stanley's misanthropic

image to project a hero as decent as Bill Harford.) The colors are exquisite,

glowing and pulsing, soothing, like some lavish opium-dream version of The

Nutcracker, reminiscent of such movies as Fanny and Alexander,

Lola Montés, Vertigo, One from the Heart (which

was originally conceived as the first X-rated film to use big stars), and

any number of films by Vincente Minnelli and Michael Powell. Those eloquent,

discreet fades that Stanley has always been the master of have never been

more dramatic. As film, Eyes Wide Shut has all of the qualities that

you’d think movie critics would look for, pray for, sit through many

hours of completely empty viewing hoping to one day enjoy, and it all sailed

clean through their nets. All that remained to seal their aversion to Eyes

Wide Shut was a happy ending, and it also had that: standing in the middle

of a toy store, speaking the verities that are at least as old as marriage

and with no guile whatsoever, like characters at the end of a children's play

or the closing moments of The Magic Flute, having passed through their

ordeals successfully, having told each other "everything," Bill and Alice

are ready to go home for a heart-to heart fuck and a refreshment of their

vows.

I know that it's only

a movie, and if it's a masterpiece (as I'm sure it is), that's all that it

is, another masterpiece. As rare as they are, somehow the world is teeming

with them. If the process of making them had stopped a hundred years ago,

and there had been no Joyce, no Picasso, no Faulkner or Frank Lloyd Wright,

Schoenberg or Ellington or Hitchcock, we would still have far more masterpieces

than we'd ever have time to deal with. Maybe (and wouldn't it be pretty to

think so?) that's what happened with Eyes Wide Shut and the critics;

maybe they weren't suffering from art-phobia at all, maybe it was only

masterpiece fatigue.

In any event, I won't

offend their sense of perfection by suggesting, except very quickly, that

flaws can make a masterpiece even more lovable. All of Stanley's movies were

flawed, along with just about everybody else's. The Shining is famously

flawed, and I've never had any idea at all what he thought he was doing in

the second half of Full Metal Jacket, with the mood swings and the

flat satirical intrusions, none of which diminishes its greatness. Not only

is Eyes Wide Shut a flawed masterpiece, like War and Peace and

Mahler's Eighth (and, come to think of it, Fidelio), I believe

it's an unfinished masterpiece, like The Castle and the Mozart Requiem,

no matter what was said at the time of Stanley's death. He would have fiddled

and futzed with it right up to the moment of release and beyond, if he thought

he could tune it any finer.

|

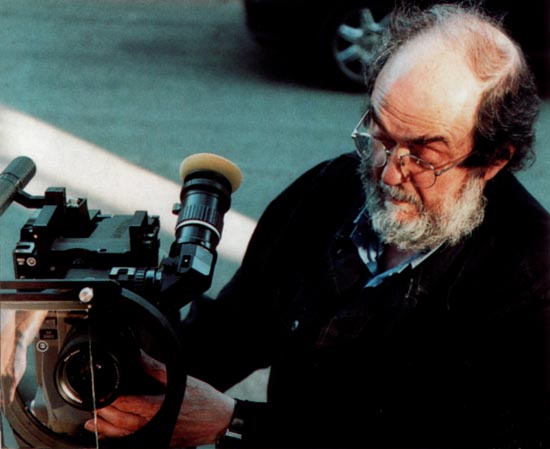

PARTY

PLANNING

Kubrick,

Cruise, Kidman, and Pollack study replays on the huge Christmas party

set.

|

Not concerned

with blood and iron this time, or conflict on a cosmic scale, Stanley

was in the mood for love.

|

He might, for example,

have done something about what I can only call the "repetitive device" in

the dialogue, a line from one character repeated by another, usually in the

form of a question: "He moved to Chicago." "He moved to Chicago?" "I had you

followed." "You had me followed?" "It was fake." "Fake?" "Yes, fake" - seemingly

dozens of times, so many of them that you feel the script would have been

half as long without them. They're clearly deliberate, but I can't imagine

why, unless possibly to suggest the power of sexual confusion, the worst confusion

there is, the only exception I can think of being the confusion experienced

in dreams. He probably would have trimmed the undeniable longueurs, like the

scene near the end where Tom Cruise and Sydney Pollack circle a Matisse-red

pool table for what feels like an hour and seem to explicate all the things

in the "story" that should never be spoken of. I don't know what to think

of it; no man could have wished it longer, and though it's an incredibly interesting

scene in many ways, I don't even know what it's supposed to be about, unless,

as I suspect, it's really just about the red pool table. You could always

count on Stanley every time to vote for Beauty over Content, since he didn't

think of them as two separate things.

Mark Twain called nostalgia

"mental and moral masturbation," meaning, I'll guess, the unhealthy, somewhat

selfish, totally uncreative uses of the past, the truth of your history cannibalized

for the purposes of sentimentality, pissed away for candy. (It's the element

that kept the larger wheels of cinema greased for a hundred years, it's the

glop that drips from every orifice of the culture, clogging all our arteries

of discrimination.) I hope, then, that I won't be thought a nostalgic fool

if I insist that even in my lifetime there was a much more attractive culture

than the one we're enjoying now.

They speak about the dumbing

of America as a foregone thing, already completed, but, duh, it's a process,

and we haven’t seen anything yet. The contemplation of this culture is

not for sissies, and speaking about it without becoming shrill is increasingly

difficult, maybe impossible. In spite of this, even for those of us who were

most attached to it, there are better things to do than cling to the wreckage

of the liberal-humanist literary culture that seemed so invincible and irreproachable

only 30 years ago, to forever pick over the debris and salt it with our tears.

Nevertheless, I can understand why people miss it. At its most radiant, it

didn't just shine its fight into literature, it suffused all the arts, the

movies most of all.

The Art-House Transmission

that Stanley received so deeply in the 40s was still manifesting in the early

60s, when I spent my nights and a lot of afternoons rocketing between the

Bleecker Street Cinema, the Thalia, the New Yorker, and the Museum of Modem

Art, running after the hundreds of films that had been unavailable to me living

upstate, in the provinces. Films by Ingmar Bergman, Alain Resnais, Akira Kurosawa,

Max Ophüls, Satyajit Ray, Michelangelo Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Luis

Buñuel, Robert Bresson, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Melville, Federico

Fellini, to say nothing of Douglas Sirk, Fritz Lang, Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas

Ray, Sam Fuller, and not forgetting the final films of John Ford and Howard

Hawks and Jean Renoir, blew in and out of New York with great velocity and

frequency. It's amazing how much luster those names had, and for how many

people. They kept that arbitrary rectangle brimming with drama and spectacle,

nuance and magic. And so if I got weepy when the end credits rolled on Eyes

Wide Shut and the waltz played one more time, it wasn't because a movie

was over, or because it was the final work of a man I admired and loved, but

because that tradition, with its innocence, or anyway its naïveté,

and a purity that only someone born before 1930 could continue, had come to

a certain end, as most traditions do. It's gone and it won't be returning.

|

|

|

THE

WIZARD

Stanley

Kubrick died before Eyes Wide Shut was released, so it may be fair to say

that it is an unfinished masterpiece. |

|

You could

always tell it was a Stanley Kubrick movie the moment it started, but

he never made the same movie twice.

|

It's interesting, that

a guy who fancied himself the von Clausewitz of movie marketing, who was so

immersed in the arcana of demographics, audience profiles, and distribution

strategies, right down to the capacity and turnover of dozens, maybe hundreds,

of individual movie theaters, was also a man who made his movies totally for

himself. He was calculating, but his truest calculations were all artistic

ones. The rest, the behavior he was notorious for, was only show-business

phenomena. He didn't grumble about the bankruptcy of a world that welcomed

and actually required such manipulations, he was amused and instructed by

it, and he played the game pretty well, although perhaps not as well as he

thought. Still, no artist could help but find it objectionable.

"How can I make a movie

that would gross as much as Star Wars and yet allow me to retain my

reputation for social responsibility?," Stanley said to Brian Aldiss, whose

work they were adapting together for Al, the "Pinocchio story." I gather

Aldiss had his ups and downs with Stanley, but he tells this story with obvious

affection, and acknowledges, naturally, that Stanley was joking. As I hear

him tell it in my head, I can pick up on that very distant, almost offstage

laugh that made you wonder if you were meant to hear it or not, until you

remembered whom you were talking to. If Stanley didn't want you to hear something,

his dogs might pick it up, but not you. I've never said that he wasn't secretive,

and I would never say that he wasn't obsessive.

You could always tell

it was a Stanley Kubrick movie the moment it started, but he never made the

same movie twice. It was often said that the people in Stanley's movies live

in separate spaces on the screen, most often alone no matter what the company,

but that was something that had been in the air since the early days of the

late century; we've all breathed it, artists breathed it more deeply, and

exhaled it as work. It is through those spaces, and in the distances between

them, and their arrangement on the screen, that you can find the essence of

Stanley's sympathy, a valuable quality that he had but that not very many

people thought that he had, and which was made even more valuable by his detachment.

In all of the media's mischief and misapprehension, there was a lingering

innuendo that he only made movies to get himself through a bad case of chronic

social anxiety disorder, but in fact he had his friends, many of them, who

tell another story. An artist's isolation has nothing to do with physical

circumstances anyway, with how publicly or privately he seems to be doing

his work. It's more about tempo, intuition, experiment, and the land of silence

you don't come by easily these days, and not at all if you're passive. Out

of this situation, the only situation he could tolerate, he made films of

an incredible purity.

He was often enough dismissed

as an inspired mechanic by people who were unaffected by his work. He knew

the mechanics as well as anybody, better than a lot of actual mechanics, but

he only bothered to master them because of their value to his purpose, the

way writers try to learn their language in some manner that is functional

and more than functional. Diane Johnson, the novelist who co-wrote The

Shining, has spoken of his "chaste and rigorous view of art," and Garrett

Brown, the inventor of the Steadicam and Stanley's partner in a technological

marriage made in heaven, recalls, "We had discussions about the elusive quality

of perfection." I'm absolutely certain that they did. It was Stanley's subject.

Michael Herr

VANITY FAIR

April 2000